Plasma – Why do some centers pay for plasma and others don’t?

What should you consider in making a choice in where to donate?

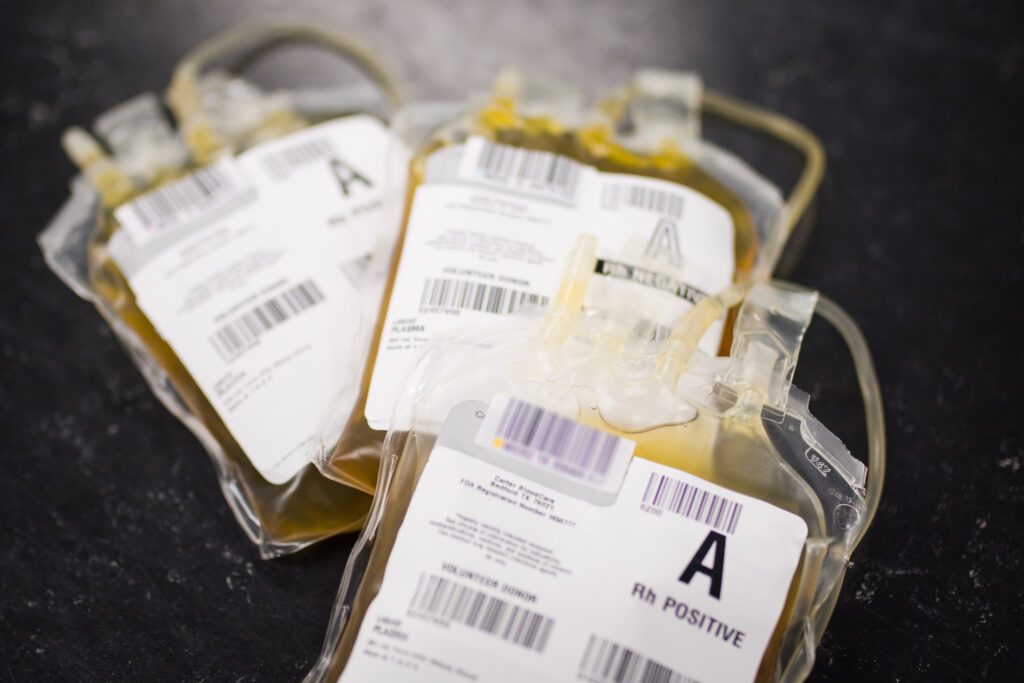

By Carter BloodCare

Plasma is the liquid part of the blood, used for treating bleeding and other disorders. Donated plasma may go directly to hospitals after testing and labeling at the blood center. This is the type of plasma donation in which Carter BloodCare participates. Other than having an anti-clotting agent added, the plasma is not altered in any way – it is transfused to the patient in the same state it was collected from the donor.

People may choose to instead go to a commercial plasma center where they can “donate” plasma for money. This plasma is shipped to a manufacturing plant where it is pooled with plasma from 1000 or more other “donors” then processed to make products called plasma derivatives. These products, usually made in locations outside of the United States, are vital to medical treatments all over the world, including the United States, but are a highly processed product. I put “donor” in quotation marks because if one is selling plasma, then one might be considered a vendor, not a donor.

Historically, the paying of donors has been seen as a risk to the safety of the traditional blood supply for hospitals. Any time an incentive for a successful plasma donation is offered that is too attractive, the fear is that donors might not tell the truth about their health history or any high-risk behaviors. The Food and Drug Administration does not ban the paying of blood donors, but requires paid donors to have labeling that identifies the unit as coming from such. Hospitals in the United States have traditionally favored blood from non-paid donors and request blood from volunteer donors. Scientific studies in years past showed higher infectious disease rates in donors that were paid, than in unpaid donors. Thus the standard of practice in the United States for the last 30 years or so has been to transfuse blood from volunteer donors, instead of donors selling plasma. Further, nearly all blood collection centers for hospital red cells, platelets and plasma in the United States are non-profit organizations with minimal revenue margins that would be hard-pressed to pay donors more than t-shirts or other trinkets.

Commercial plasma centers are able to take extra safety steps that community blood centers cannot. Because the plasma sent for manufacturing is going to be processed, it can be held until the “donor” returns to donate again in weeks to months and additional plasma is collected. This way the infectious disease testing is repeated before the plasma is sent off and the safety of the donor can be assured. In addition, the pooled batch of plasma at the manufacturing plant will be treated with chemicals or heat to inactivate most infectious organisms. This treatment does not damage the final plasma derivative products. By comparison, plasma used directly at the hospital does not usually have this treatment performed. Therefore, the community blood center tends to be more vigilant about attracting donors for altruistic purposes only, not for the money.

When choosing which place to donate, ask yourself what your motivation is. Are you asking, “How much do you get for donating plasma?” or “How many people can you help?” There is no substitute for the plasma donations needed to treat trauma patients, burn patients, transplant patients, and patients with liver failure. On the other hand, the plasma collected by the commercial plasma center is going for a good cause, too – the plasma is needed for products such as immune globulin, albumin concentrate, and clotting factors. There is no doubt that those are also in need, and some will come back for local patients. But each type of plasma collection demands a different type of donor. Which are you?

Find out what it takes to #GiveForLife and help patients in North, Central and East Texas.

Read our FAQs or call/text 800-366-2834.

Donate Today!

Reference

Paid-versus-volunteer blood donation in the United States: a historical review. RE Domen. Transf Med Rev 1995, 9(1):53-59.